Brad Pillans, Director, National Rock Garden

Published in the National Rock Garden Newsletter No. 26, December 2023

As you will read, in this newsletter, it has been a busy year for the NRG, with several new rock acquisitions (and more to come in 2024). We also made substantial progress towards moving to our new site within the National Arboretum Canberra, where a ‘Coming Soon’ sign has now been erected (Figure 1).

To assist our move to National Arboretum, I am delighted to announce that the Minerals Council of Australia (MCA) has recently donated $80,000 towards construction costs. This generous donation from the MCA, which is a Partner of the NRG, will enable us to establish the first rock displays at the new site early in 2024. High priorities include construction of an Indigenous welcome feature and transfer of our popular Federation Rocks from their current display site in Lindsay Pryor National Arboretum.

The indigenous welcome feature is being developed in consultation with Ngunnawal Elder, Dr Caroline Garuliiny Hughes AM. In September, Dr Hughes, selected a group of four beautiful, rounded boulders (tors) of local volcanic rock for inclusion in the welcome feature (Figure 2). As we admired the rocks, two wedge-tailed eagles were soaring nearby, almost as if they were giving their approval for the choice [the wedge-tailed eagle is a totem of the Ngunnawal people].

Three recent additions to the NRG collection are described later in this newsletter:

- silcrete from Shannons Flat, just over the ACT border on the road to Adaminaby, NSW

- red ribbon chert from Chaffey Dam, near Tamworth, NSW

- witherite (barium carbonate) from the Rosebery mine in Tasmania.

Each of these three rocks have interesting stories to tell, but I’d like to elaborate on the first.

Silcrete is a near-surface equivalent of quartzite—both are rocks cemented by silica, but whereas quartzite is a metamorphic rock, formed at depth at high temperature and pressure, silcrete is formed near the surface at low temperature and pressure. Despite being a widespread rock type in Australia, its mode(s) of formation is (are) debated. It is very common in central Australia, where it often occurs forms high points in an otherwise flat landscape because of its resistance to erosion. Fossil leaves are sometimes preserved in silcrete, which provides a window into the types of plants that grew in the area when the silcrete formed (Figure 3). The hardness of silcrete also made it an attractive building stone – in northern South Australia, north of Goyder’s Line, the landscape is dotted with the ruins of abandoned houses, often built of silcrete (Figure 4).

Goyder’s Line

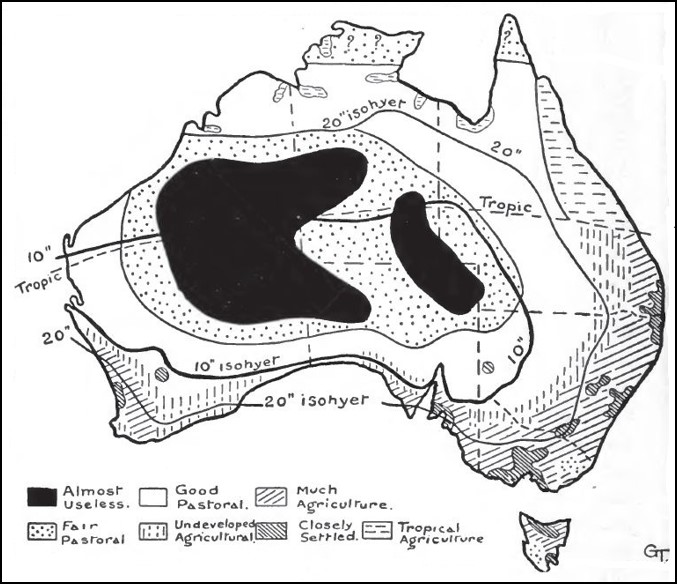

In 1865, George Goyder, Surveyor General of South Australia, recommended against farming north of a line broadly corresponding to the 10” (~250mm) isohyet of modern annual rainfall. The line also marks a change in vegetation—from mallee scrub in the south to saltbush in the north. Areas north of the line were judged to be liable to drought and farmers were advised not to plant crops in this area. Coincidentally good rain fell in most years from 1867 to 1875, and Goyder’s recommendation was ignored by farmers who pushed their crops ever further north. When rainfall patterns reverted to normal, many farms were abandoned. Decades later, well-known geographer Griffith Taylor, published a map (Figure 5) showing the suitability of Australia for agriculture, echoing the ideas of Goyder. I have always loved Taylor’s bluntness in labelling large parts of Central Australia as ‘almost useless’.

For some years, I have known about a spectacular outcrop of columnar basalt at Fingal Head in northern NSW (Figure 6). In August, my wife, Sue, and I did a road trip to Brisbane, and I was able to tick Fingal Head off my bucket list. The basalt is thought to have erupted from Tweed Volcano, around 20 million years ago. The name Fingal is a nod to the Giant’s Causeway in Ireland and Fingal’s cave in Scotland, at either end of a basalt lava flow, with similarly spectacular columns, that extends across the Irish Sea— mostly underwater, of course. Although we don’t have a specimen from Fingal Head in the NRG collection, we do have some nice basalt columns from the Gosford area of NSW.

Meanwhile, back in Canberra, we like to keep in touch with our local politicians. David Smith MP is the Federal member for the electorate of Bean, in Canberra, and is an enthusiastic supporter of the NRG (Figure 7). Last month, I attended a Volunteer Recognition event at Parliament House, hosted by David. NRG Steering Committee members, John Bain and Marita Bradshaw also attended, and we all had a chance to talk with David about the NRG, including our desire to source a rock from Norfolk Island, whose residents are David’s constituents. Needless to say, David was very receptive to the idea!

I wish all Friends of the National Rock Garden a safe and happy Christmas and look forward to seeing many of you at the NRG in 2024.