Brad Pillans, Director, National Rock Garden

Published in the National Rock Garden Newsletter No. 25, May 2023

People like dressing up on Norfolk Island, especially in 19th century uniforms, as my wife, Sue, and I discovered when we were there on holiday recently. Our visit coincided with Norfolk Island Founders Day, which included a re-enactment of the arrival of the first convicts (and soldiers) on 6 March 1788, led by Lieutenant Philip Gidley King, aka well-known local resident, Brooke Watson. This photo (Figure 1) shows me (not dressed for the occasion, sadly), with Brooke, after the flag-raising ceremony on Founders Day.

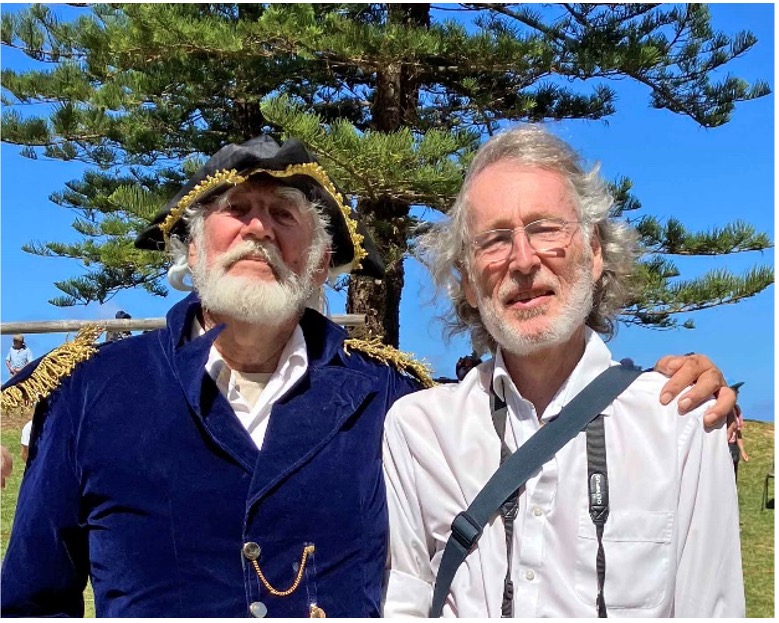

Norfolk Island is a little Aussie outpost that is closer to New Caledonia and New Zealand than it is to Australia. Indeed, the island, which is only 6 km in diameter and just over 300 metres above sea-level at its highest point, is part of the large, mostly drowned continent of Zealandia (Figure 2). Little is known about the rocks that occur underwater along the Norfolk Ridge, a major bathymetric feature that links New Zealand and New Caledonia. However, based on rock exposures in New Caledonia and New Zealand, the rocks of the Norfolk Ridge are presumed to be similar, i.e. sedimentary, and metamorphic rocks of Mesozoic age (Mortimer et al., 2021). Several seamounts (undersea volcanoes) occur on the western flank of the Norfolk Ridge—dredge samples from these have been dated to between 21 and 31 million years (Mortimer et al. 2021).

Norfolk Island and nearby, but much smaller, Phillip Island, are the only emergent part of the Norfolk Ridge, and are largely built of basalt, erupted from sea floor volcano around 2 to 3 million years ago (Jones & McDougall, 1973). There are extensive outcrops of basalt in the coastal cliffs, and large basalt boulders occur on many beaches (Figure 3). Perhaps we could bring one or two to the National Rock Garden? More on that later…

With plentiful rainfall (1300 mm/year) and fertile basalt soils, it is no surprise that Norfolk Island is home to rainforest vegetation that shares many similarities with New Zealand. Throw in the endemic Norfolk Island Pine (Araucaria heterophylla) and the result is a stunningly beautiful, but distinctive ecosystem, devoid of native mammals, with birds as the dominant land animals. [Rats and rabbits came with Polynesian and European settlers, respectively].

Captain Cook ‘discovered’ Norfolk Island in 1774. Polynesian people had lived there hundreds of years before, but had abandoned the island by the time Cook arrived, leaving little trace except bananas (plantain or cooking bananas) that they had planted (Polynesian rats also stayed behind). Archaeological investigations subsequently revealed that Polynesian colonisation occurred in the 13th and 14th centuries, most likely from either New Zealand or the Kermadec Islands (Anderson & White, 2001). Stone artefacts, including adzes were made from local basalt, with obsidian being sourced from Raoul Island in the Kermadecs. Current research, led by archaeologists from the Australian Museum, is revealing further information on these artefacts (Vince, 2022).

Within weeks of the First Fleet arriving in Australia in January 1788, Governor Arthur Philip ordered Lieutenant Philip Gidley King to lead a party of 15 convicts and seven free men to take control of Norfolk Island—they arrived on 6 March 1788 and that date is celebrated as Founders Day on Norfolk Island. More convicts (and soldiers) followed, and Norfolk Island operated as a penal colony until 1814, when it was abandoned, and all buildings were destroyed to prevent any inducement for other European powers (the French in particular) to move in.

From 1814 to 1824 the island was uninhabited, but then the British decided to have another go, and Norfolk Island was reoccupied as a place to send the worst convicts. This second penal settlement lasted until 1855, when the island was abandoned yet again. Most of the stone buildings in the historic Kingston area date to this period (Figure 4). In 1840, Alexander Maconochie became commandant of the penal colony and was known for his more humane treatment of the convicts—the Canberra jail is named after him—but after he left in 1844, commandants reverted to the former regime of brutal terror.

The next settlement began on 8 June 1856, as the descendants of Tahitians and the HMS Bounty mutineers, including those of Fletcher Christian, were resettled from the Pitcairn Islands, which had become too small for their growing number.

Today, the population of Norfolk Island is around 1,800, and the most common surname in the Norfolk Island phonebook is Christian! Tourism is the mainstay of the island’s economy, as Sue and I can attest. A lasting impression is how friendly everyone is—a local custom is for drivers to wave to other drivers on the road. And there is no crime, no graffiti and people don’t lock their cars or their houses. Our accommodation package included a complimentary hire car—I never did find the electronic key fob, but it was in the car, somewhere, and that was all that mattered, according to our hosts!

Norfolk Island was self-governing from 1979 to 2015, and Sue and I were fortunate to meet David Buffett, the last Chief Minister, while we were there (Buffett is also a Pitcairn name). The island is now administered by NSW, but there is also a curious Canberra connection—Norfolk Islanders vote in the Canberra-based Federal electorate of Bean, with David Smith as their MP.

A Norfolk Island rock for the National Rock Garden?

Last year, Mike Smith also visited Norfolk Island, and initiated discussion with David Buffett regarding the possibility of obtaining a rock or rocks from Norfolk Island for the NRG. David was very supportive of the idea and remains so after my visit this year. There are two major rock types on the island—basalt and calcarenite. Basalt is overwhelmingly the dominant rock type, but on the south side of the island, there are extensive outcrops of calcarenite—a kind of soft limestone composed of fragments of shell and coral, which were washed up on the beach and later cemented by calcium carbonate derived from partial dissolution of the shell and coral fragments (Figure 5). The calcarenite was extensively used as a building stone for all convict-era buildings on Norfolk Island (Figure 4).

My recommendation is that we bring both basalt and calcarenite to the NRG, to represent Norfolk Island. Suitable large basalt boulders are readily available on beaches (Figures 3 and 6) and scattered through the interior of the island (Figure 7). However, outcrops of calcarenite only occur within the World Heritage listed area of the island, and on Phillip Island, more correctly referred to as an islet (area about four hectares), just offshore, both areas of which may present logistical difficulties for acquisition of a suitable specimen for the NRG. Alternatively, it may be possible to obtain a calcarenite building stone from a ruined building or stone wall elsewhere on the island.

Transport of Norfolk Island rocks to Canberra is also a logistical difficulty to be overcome. Supply ships come to Norfolk Island approximately monthly, and cargo is unloaded at one of two jetties, on opposite sides of the island, depending on sea conditions. However, the supply ship cannot dock at the jetties and a smaller boat is used to ferry cargo from ship to shore (Figure 8). I did not establish the maximum size/weight that can be loaded/unloaded, but cars were being unloaded when I was there.

References

Anderson, A., White, P. (Eds.), 2001. The Prehistoric Archaeology of Norfolk Island, Southwest Pacific. Records of the Australian Museum Supplement 27. Australian Museum, Sydney, 141 pp. https://doi.org/10.3853/j.0812-7387.27.2001.1334

Vince, C., 2022 (October 29). Priceless archaeological artefacts found in Norfolk Island National Park by local citizen scientist. Australian Museum. https://australian.museum/about/organisation/media-centre/archaeological-artefacts-norfolk-island/#:~:text=Norfolk%20Island%20National%20Park%20Manager,island%2C%E2%80%9D%20Mr%20Greenup%20said

Jones, J.G., McDougall, I., 1973. Geological history of Norfolk and Philip Islands, southwest Pacific Ocean. Journal of the Geological Society of Australia, 20(3): 239–254. https://doi.org/10.1080/14400957308527916

Mortimer, N. et al., 2021. The Norfolk Ridge seamounts: Eocene–Miocene volcanoes near Zealandia’s rifted continental margin. Australian Journal of Earth Sciences, 68(3): 368–380. https://doi.org/10.1080/08120099.2020.1805007